Rethinking advance care planning

While more physicians are reporting having conversations about advance care planning with their patients, it's still far from common.

In 2016, CMS began allowing physicians to bill for advance care planning during outpatient visits, waiving copays when these discussions took place during Medicare's Annual Wellness Visit. Six years later, outpatient advance care planning has become more common, but rates remain low. In addition, some debate exists about the role of legal advance directive forms in patients without serious illness.

Advance care planning discussions often, but not always, lead to development of advance directives, which include living wills and power of attorney for health care. The most recent edition of ACP's Ethics Manual, published in Annals of Internal Medicine in January 2019, notes that “Physicians should routinely raise advance planning with adult patients with decision-making capacity and encourage them to review their values and preferences with their surrogates and family members. …These discussions let the physician know the patient's views, enable documentation of patient wishes in the medical record, and allow the physician to reassure the patient that he or she is willing to discuss these sensitive issues and will respect patient choices.”

Recent research found that while more physicians are reporting having these conversations with their patients, it's still far from common. An analysis of Medicare fee-for-service data published in Health Affairs in April 2021 showed a substantial increase in outpatient advance care planning claims between 2016, when CMS introduced codes to allow billing for the service, and 2019. However, overall use of the codes remained below 7.5% in all patient subgroups, including age, sex, and ethnicity. In addition, in an analysis published in Health Affairs in January 2022, physicians, administrators, and key hospital leaders reported a number of barriers, including ethical and workflow concerns, said lead author Keren Ladin, PhD, associate professor and director of the Research on Aging, Ethics, and Community Health (REACH) Lab at Tufts University in Boston.

While one aim of advance care planning is to increase provision of high-value, goal-concordant care, results in the literature for these outcomes tend to be negative, said Robert M. Arnold, MD, FACP. He pointed to a series of systematic reviews and randomized trials that failed to show an association between advance care planning and subsequent health care use or goal-concordant care. For example, a cluster-randomized trial at 23 hospitals in Europe, published in November 2020 in PLOS Medicine, looked at the use of scripted advance care planning conversations between patients with cancer, family members, and certified facilitators and found no change in quality of life between the intervention and control groups and no change in symptoms, coping, or patient satisfaction. In addition, 16% of patients said they found the advance care planning conversations distressing.

“Advance directives are a very broad category of conversations that often occur with people way before they face life-limiting decisions,” said Dr. Arnold, a palliative care physician and medical ethicist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center who coauthored an Oct. 8, 2021, JAMA Viewpoint article questioning the impact of advance care planning on the quality of end-of-life care. “The data suggests that those conversations may not have the impact that we wanted them to have when advance directives were first developed.”

Focus on surrogates, satisfaction

Given the research, advance care planning discussions should focus on engaging patients who are seriously ill and asking them to choose a surrogate decision maker in case they should lose the ability to make their own decisions, said Diane E. Meier, MD, FACP, a palliative care physician at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and a coauthor with Dr. Arnold on the JAMA article.

“Most of us will lose the ability to make our own decisions during a serious illness, and therefore we need to have someone we trust to make decisions,” Dr. Meier said. “Just thinking of who that person might be is not sufficient. You have to actually talk to that person and ask them if they're willing and tell them what you would want if you were unlikely to recover to be able to recognize and interact with your loved ones. Some of my patients say in that situation they would want care focused on their comfort, and others say they would still want treatment focused on living as long as possible. Which kind of person are you?”

Having these types of conversations too early or focusing too narrowly on specific types of interventions, like feeding tubes or ventilators, is not useful, Dr. Meier explained. Most people would say yes to these interventions if they were only needed short term, for a week or two. Also, despite believing they would never want to be kept alive on machines, people often change their minds in favor of these treatments when they get sicker or when death is imminent. “The whole notion of advance care planning ignores the reality that we can't anticipate our future ability to adjust and accept constraints on our life that at an earlier stage of life would have seemed unacceptable,” she said.

Rebecca Sudore, MD, a geriatrician at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that designating a surrogate decision maker is important but said it's also relevant for younger, healthy people since accidents or illness can happen at any time. Once a surrogate is chosen, the focus of advance care planning should be on preparing both the patient and the surrogate for medical decision making by focusing on what quality of life means to the patient, she said.

Dr. Sudore said she is not surprised that some of the research on goal-concordant care is mixed, because standardized measures are lacking. However, she noted that updated data from randomized controlled trials over the past decade show that advance care planning decreases surrogate distress. She coauthored a scoping review published in September 2020 in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society showing that while advance care planning appeared to have varying effects on health care utilization and goal-concordant care, it was consistently associated with higher patient and surrogate satisfaction with communication and medical care and less surrogate and clinician distress.

“When you ask patients, ‘What is your motivation for doing advance care planning?,’ nine times out of 10 they say that they want to decrease burden on their family members and friends. That's what the research evidence is showing that advance care planning is doing,” Dr. Sudore said. “It may not have decreased health care utilization, but I would say that it's doing something incredibly clinically meaningful.”

ACP Member Angelo Volandes, MD, a physician-researcher and medical ethicist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, said that the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the urgency around advance care planning, particularly for African-American and Hispanic communities who were disproportionately affected by the virus.

“The criticism has been that this is all hypothetical and people don't really think this makes any difference. That's different in a post COVID-19 world where people have died,” Dr. Volandes said. “Your neighbor has died; that person who was sitting next to you at church is no longer there. When you're bringing up this conversation, it is for real. It is in-the-moment decision making.”

Dr. Volandes and colleagues recently tested a video education intervention among more than 15,000 older patients in a single New York health care system to see if it would improve uptake of advance care planning documentation. They coupled this with clinician training in communication skills. The study, which was conducted before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, also focused on results among African-American and Hispanic patients.

The results, published in JAMA Network Open in February, found a significant uptick in advance care planning documentation, from 17.9% in the pre-COVID period to 23.8% during the intervention period. Among African-American patients, that number jumped from 18.1% to 30.0%. Similarly, advance care planning among Hispanic patients increased from 13.2% to 21.2%.

Dr. Volandes, who is co-founder of ACP Decisions, a nonprofit foundation that partners with health care systems to implement patient-centered advance care planning, said the findings show the need to focus on giving tools to patients and empowering them to raise the issue of advance care planning themselves. Going forward, Dr. Volandes said advance care planning should be discussed with anyone over age 65, people with serious illnesses, and patients from underserved communities.

Simple scripts, open questions

Time can be a barrier, so Dr. Sudore suggests that internists consider breaking the conversation up into smaller pieces rather than trying to tackle everything at once. While brief conversations won't qualify for Medicare reimbursement, which requires at least 16 minutes per visit, they might allow clinicians to fit the discussions in. She also noted that advance care planning and billing can be a “team sport”: A billing clinician can initiate the conversation and enlist a nonbilling team member to help deliver part of the service with ongoing, direct supervision.

“Let's be real here. In outpatient primary care, there is no time,” Dr. Sudore said. “All these questions don't have to be asked at one time. You can ask one question, document the patient's responses, and, as in a relay race, maybe your documentation will be picked up by the social worker or a pulmonologist, or maybe you're the one who's going to pick it up next time.”

She also suggested using patient-friendly resources that allow patients to educate themselves at home and to consider what quality of life means to them. Dr. Sudore developed the evidence-based “PREPARE for Your Care” program, which offers tips to patients for choosing a surrogate decision maker, and video stories to help them think about their quality-of-life and care wishes. It also guides patients through filling out easy-to-read PREPARE advance directives. The forms are free, legally valid, and available in multiple languages for all U.S. states, Dr. Sudore said.

Another barrier can be that physicians don't know how to start the conversation. Thomas Smith, MD, FACP, director of palliative medicine for Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore and the Harry J. Duffey Family Professor of Palliative Care, said a standard script can help.

“I realized as a breast cancer oncologist I had a standard spiel for adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery or before surgery,” Dr. Smith said. “When it came to much more difficult discussions, I didn't have a simple, easy script to follow.”

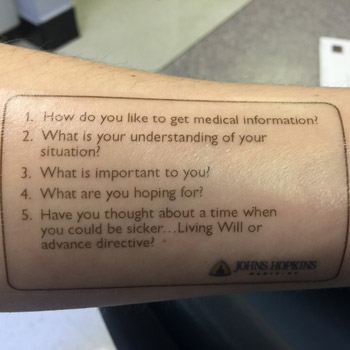

Dr. Sudore noted that PREPARE offers simple advance care planning scripts for interdisciplinary clinicians to make it easier to talk to patients about advance care planning in busy outpatient clinics. Dr. Smith has developed his own simple script, and over the years he has handed out more than 10,000 copies of it to clinicians and trainees. He also made it into a temporary tattoo that he puts on his forearm. The script has five questions for patients:

- How do you like to get medical information?

- What is your understanding of your situation?

- What is important to you?

- What are you hoping for?

- Have you thought about a time when you would be sicker, and do you want to prepare a living will or advance directive?

“Don't be afraid to bring up the issue,” Dr. Smith said. “Although we are hesitant to bring up these issues, most of the time it turns out to be a real bonding experience between the internist and family and patient, leading to more trust and more respect.”