College Fellow's foundation helps support health care workers

For many people, retirement means a chance to improve one's golf handicap and vacation in Europe. For Larry Crook, MD, FACP, it meant setting up a nonprofit to help people halfway around the world.

For many people, retirement means a chance to improve one's golf handicap and vacation in Europe. For Larry Crook, MD, FACP, formerly chief of internal medicine at the Gallup (N.M.) Indian Medical Center, it meant setting up a nonprofit to help people halfway around the world.

Dr. Crook, 68, is the president and co-founder of the Thai Burma Border Health Initiative, which helps fund and support local medics working in a medically underserved area in Burma (Myanmar) near the Thai border. The foundation, formed in 2007, sprang from a need Dr. Crook saw after working in the area with Doctors Without Borders alongside his wife, Nonnie, who is a nurse.

“After we left, I went back a couple years later to visit the local staff I'd worked with, and by that time Doctors Without Borders had pulled out of the area after more than 10 years. The local staff were then without jobs, and they wanted to know if I could help them,” Dr. Crook said. “So I came home and founded the organization, primarily to put the local staff back to work.”

His career up until his Burma experience had been spent largely with the Indian Health Service (IHS), though it was punctuated by 2- and 3-year stints in Kazakhstan and the Caribbean and volunteer experiences elsewhere.

“I just felt like I didn't want to spend 15 years in a row sitting in Gallup,” Dr. Crook said. “A lot of people [at the IHS] had international experience, but they had settled there because it was the closest you were going to get to international health inside the U.S. and still have a job and a family and a life.”

When he was younger, Dr. Crook stayed closer to home. He attended medical school at the University of Oregon (now Oregon Health & Science University in Portland) after growing up in Portland. A summer spent shadowing physicians at clinics in rural Appalachia after his third year of medical school changed his outlook, however.

“That experience in Appalachia sort of opened my eyes that there were things you can do that were more fun, more rewarding, than money-making,” said Dr. Crook. “There was a whole world out there I hadn't paid attention to.”

After a year of internal medicine residency at St. Vincent's Hospital in New York City, 2 years in the Air Force, and 2 more years of residency at Emmanuel Hospital in Portland, Ore., Dr. Crook took his first post-training job as a doctor in Nigeria with a nongovernmental organization from 1977-1978.

“In those days there was an organization, like an employment agency, that would fit people with medical volunteerism overseas. So I went to them and got a couple of offers in different places, including the Caribbean. But Nigeria was kind of the furthest away and most exotic,” Dr. Crook said. “It was pretty wild and ill-thought-out, but it was a real experience.”

He and his wife set up wards in a clinic run by 3 nuns. When Nonnie became pregnant, they returned to the United States, with Dr. Crook taking a position at the IHS. He spent 2 years there, gave private practice a whirl for a couple of years, practiced in the Caribbean for 3 years, then returned to the IHS for good, eventually becoming the chief of internal medicine.

As a commissioned officer, he was able to retire after 20 years of service with the IHS. This led him to sign up with Doctors Without Borders, which sent him and his wife to Thailand in 2003 to provide care to internally displaced people from Burma who were living in the border region. Many were from the Mon tribe, which controlled the area and had a cease-fire with the Burmese army, with whom they had been fighting since the end of World War II.

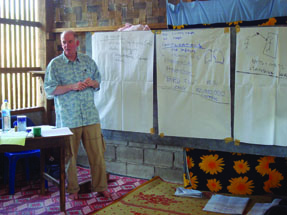

“The project was providing health support and material supervision for hospitals inside Burma,” Dr. Crook said. “We'd go into the border area during the day and visit the hospitals and make rounds and do education for the local staff, then come back home to Thailand in the evening.”

It was tricky, he added, because part of the Mon's cease-fire agreement with the Burmese government stipulated there would be no international health in the area. “We weren't supposed to be there, and the Mon people were always worried we'd be discovered. But everyone knew—I'm sure the government knew—and it was sort of tolerated at a low level,” Dr. Crook said.

The main conditions he and his colleagues treated were malaria, tuberculosis, infections, minor trauma, and some HIV. “We didn't have the ability to give antiretrovirals, but we saw a lot of people with HIV. Malaria was a big killer; we saw a lot of bacterial infections, pneumonia, urine infections, a lot of trauma,” he said.

The hands-on experience was instructive when it came time, a couple of years later, to form his foundation to support medics in the same area of Burma where he worked with DWB. One of the main things he and his colleagues have done is to help educate the local health workers about when a patient can be treated at local clinics and when he or she needs to be taken over the border to Thailand for more intensive care.

“There is actually a lot of health care available inside Thailand, so for emergency things like surgery, we can bring people in from Burma and have them cared for there,” he said. “The hospitals are more secure, and I know them. I don't know the hospitals in Burma, but I understand they are not good.”

The Thai Burma Border Health Initiative started with 1 local health worker in 2007 and now has 20. In addition to working at clinics and helping with transport to Thailand, the workers provide care in villages for people with chronic diseases, such as AIDS and tuberculosis, and offer preventive services such as immunizations, prenatal and postpartum care, and family planning. All along, the organization's approach has been to support the local residents in their work, rather than bring in U.S. workers or notions about what should be done, Dr. Crook said.

“All the day-to-day decisions are made by our project director in Thailand. The whole point was to make it their project, so they have ownership of it. They make the decisions on what projects they want to do, and [our foundation is] more about advising and funding them,” he said.

One hundred percent of the funds raised for the foundation are sent overseas. Neither Dr. Crook nor the other 3 board members—Bruce Tempest, MD, MACP, Jonathan Iralu, MD, FACP, and Jean Offner, MD, FACP—are paid for their work, and if they travel to Burma to check on the project, they pay their own way.

Someone usually visits every year for about a month, Dr. Crook said. Otherwise, the U.S. board members keep in touch with the local workers via Skype. But there is little need for oversight at this point, he added. Over the last few years, the workers in Thailand and Burma have taken on more and more of the responsibility for fundraising, such that about three-quarters of the foundation's $100,000 annual budget is now generated by them.

“We are kind of reaching a point, in the next year or two, where the board must decide whether to keep going [with the foundation] or pull back and let them go on their own. When we started, we told them we would guarantee to fund them for 5 years,” Dr. Crook said. “Things are kind of reaching a place where they are able to keep going on their own, I think, which is really the goal.”

In 2012, ACP's New Mexico chapter gave Dr. Crook its 2012 Community Service and Volunteerism Award, an honor he discussed with modesty.

“We were lucky in that we knew good people at the local level to begin with. That's sort of critical, and we had that in place when we started the foundation, which is really what has made it work,” Dr. Crook said.