Decision-making rules for diagnosing PE may save lives

Early detection of pulmonary embolism is critical, which puts the primary care internist on the front lines of preventing a patient's continual deterioration that culminates in death. Patients are as likely to present in the office with symptoms as they are at the emergency department.

The importance of early detection of pulmonary embolism (PE) in the primary care setting cannot be underestimated. The National Institutes of Health estimates that when the condition is left undiagnosed, about 30% of people die, most within the first few hours of symptoms.

“The role of primary care physicians is critical because statistics would indicate that about 40% of people who die of pulmonary embolism have been seen in a health care setting with symptoms prior to their death,” said Kathleen Harper, DO, FACP, a noninvasive cardiologist at St. Vincent's Medical Center in Bridgeport, Conn. “People having recurrent emboli are seeking attempts at diagnosis; however, many do not enter the emergency room until the situation is catastrophic or fatal.”

But in fact, there may not be much of a discernible difference between a patient who presents to an emergency department with a possible PE and one who presents to a primary care office. In both cases, it is likely an emergency situation.

“Most emergency room visits are by people who could just as easily be seen in a primary care office,” said E. Rodney Hornbake, MD, FACP. “The roles of emergency room physicians and primary care physicians are quite similar: to take complaints that have not yet been evaluated and are nonspecific, and figure out if they are important to the patient's comfort and future safety.”

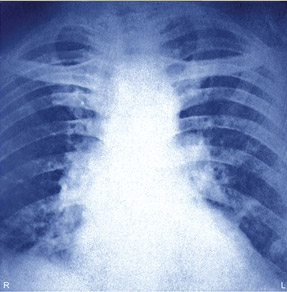

Complex diagnosis

The difficulty with diagnosing PE is that its symptoms vary from patient to patient and are frequently subtle and nonspecific.

“People can come to primary care and have something that might appear like bronchitis, asthma, flu or other types of minor respiratory illnesses,” Dr. Harper said. “The difficulty with PE is that it is a masquerader.”

Among the most commonly occurring symptoms is dyspnea, which might occur at rest or with exertion. Other nonspecific symptoms include chest pain, cough, sweating or wheezing.

“Upon exam, physicians might notice that the patient has an increased heart rate or may be breathing faster than usual,” said Wendy Lim, MD, associate professor in the division of hematology and thromboembolism at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada. “There are published clinical prediction rules that can assist physicians in determining the pretest probability of PE. In combination with additional testing, PE can be ruled in or out as a diagnosis.”

Two validated clinical prediction rules for PE include the more commonly used Wells criteria or modified Table and the revised Table 2. The rules allow physicians to score patients based on a variety of factors such as a history of venous thromboembolism, clinical signs and symptoms of deep venous thrombosis, age, heart rate, presence of cancer, recent surgery, immobilization and hemoptysis. The scores place patients into low-, intermediate- or high-risk categories. Pretest probability rules are frequently combined with a D-dimer test in low-risk patients to give the clinician a clear picture of risk and to aid in the decision to refer the patient for additional diagnostic investigations.

This combination of tools was first tested by the Christopher Study Investigators. In a study published in 2006, the investigators used the Wells criteria to classify 3,306 patients as likely or unlikely to have PE. Those patients classified as unlikely went on for D-dimer testing; those classified as likely received computed tomography. Of the 66.7% of patients classified as unlikely, 32% also had a normal D-dimer test, and of this group, only five had a subsequent nonfatal venous thromboembolism.

However, not every physician has immediate access to D-dimer testing. Dr. Hornbake said that physicians typically will have three available options to perform the test: a hospital laboratory with about a 30-minute turnaround time, a commercial laboratory with a 24-hour turnaround time, or, if the practice has sufficient volume to warrant it, a D-dimer kit for in-office use, which would have the quickest turnaround time.

“These kits have expiration dates, though, and you typically have to buy 10-packs,” Dr. Hornbake said. “If you buy a kit for $1,000 and only use it once before it expires, it does not make sense from an economic standpoint.”

In addition, D-dimer tests are not always easy to interpret, especially for someone who is less experienced with the assays. The test has a high negative predictive value, making it easier to eliminate the possibility of PE than to confirm it.

“The limitation to a D-dimer is that if it is intermediately elevated, it can be elevated for different reasons,” Dr. Harper said. “There are other disease states that can elevate D-dimer, and usually only a markedly elevated D-dimer is a clear indication of PE.”

Ringing the alarm

With such a challenging diagnosis, false alarms will occur. Dr. Lim practices at a specialized thrombosis clinic, where she said the probability of a PE diagnosis is relatively low, since many of the patients referred have a low pretest probability.

“Of all the patients that come here, we make a diagnosis of PE in about 10% to 20% of patients,” Dr. Lim said.

However, given the deadly nature of the condition, the old adage of “better safe than sorry” still applies.

“Keeping in mind that as a cause of sudden death massive PE is second only to sudden cardiac death, it is certainly a risk category that should be not overlooked,” Dr. Harper said.

Physicians should keep particularly close watch on patients older than 80 years who have a significantly increased risk for PE, according to Dr. Harper. In addition, physicians may want to give extra attention to women who are pregnant; black patients, who tend to also have increased mortality from PE; overweight patients; those who are otherwise healthy but have had a recent surgery; or those who have recently traveled for long periods involving immobility.

Going with the gut

If a physician does not have D-dimer testing or one of these clinical decision-making tools available, it is still possible to ask questions that can uncover red flags. Questions outlined in the PIER module on pulmonary embolism include the following:

- Does the patient have a history of cancer, recent trauma, surgery or a period of immobilization?

- Is the patient pregnant or taking a form of estrogen such as oral contraceptives or postmenopausal hormone therapy?

- Is there a history of venous thromboembolism in the family?

Asking these questions, as well as having an ongoing awareness of symptoms, will help to ensure that patients who may have PE get the treatment that they need quickly. However, clinicians shouldn't rely only on textbook definitions, according to Dr. Hornbake.

“For example, you may see a young woman who is reporting symptoms and has just been put on oral contraceptives, and also has a sister who had a fatal PE,” Dr. Hornbake said. “Using the Wells criteria, she would be considered low risk, and she may also have a normal D-dimer level. But using clinical judgment, a physician may still elect to do a CT scan.”

Ultimately, Dr. Hornbake said, physicians should be informed by all the evidence accumulated in the last 15 years but should not underestimate the value of their own clinical judgment.

“Admittedly, many physicians still use clinical judgment and probably incorporate some of these pretest probability algorithms informally to decide whether PE is a likely diagnosis or not,” Dr. Lim said. She added that in certain cities in Canada where there are specialized thrombosis clinics, it is routine for primary care clinicians to refer the patient to these clinics for diagnostic testing.

Whether using clinical judgment or the more proven pretest probability scores, Dr. Hornbake said that if PE is likely, treatment should begin promptly.

“The decision of how and where to treat will vary based on the physician's comfort level with treating PE,” Dr. Hornbake said. “You have to pick the fastest means of getting the first dose into the patient.”