Make path to health one of least resistance

Behavioral economics explains why patients sacrifice their long-term health for short term rewards, and suggests ways that internists can easily convince them to change.

How does someone decide whether to have a salad or ice cream with lunch? How do cancer patients choose between different courses of chemotherapy? While these questions vary greatly in their difficulty and significance, the key to understanding how people answer them lies in a still-developing field called behavioral economics.

“Behavioral economics brings together psychology and economics to better understand how people make decisions,” said Kevin Volpp, ACP Member, assistant professor of medicine and health care systems at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and the Wharton School in Philadelphia. The field grew out of some economists' recent realization that, contrary to traditional economic theory, people do not always make rational decisions or choose the course of action that is in their long-term interests.

Perhaps the best-known application of the theory is outside of medicine, in retirement planning. Instead of having employees elect to have retirement savings withheld from their paychecks, some employers have tried requiring employees to opt out if they don't want to save. Multiple studies have found that program participation is significantly higher under the opt-out programs.

The same principles easily could be used to improve the health habits of Americans, wrote Dr. Volpp and two co-authors, George Loewenstein, PhD, and Troyen A. Brennan, FACP, in a recent commentary in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“People are prone to taking the path of least resistance, so making healthy choices easy for them and adding even the smallest costs or impediments to doing unhealthy things can have a huge impact on behavior,” said Dr. Loewenstein, a professor of economics and psychology at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pa.

Short-term thinking

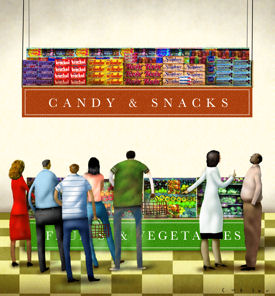

Efforts to make healthy choices easier could be as simple as rearranging a cafeteria so that the salad bar is more obvious and accessible than the dessert tray, or could entail more elaborate projects offering financial incentives. Either way, the health improvement plans developed by behavioral economists try to take advantage of two common tendencies that scientists have found in the psyches of decision-makers—opting for short-term instead of long-term gain and sticking with default options.

Weight loss and smoking cessation are two good examples of how health behavior change is made more difficult by people's bias toward immediate rewards over long-term success.

Dr. Loewenstein described the dieter's thought process. “You want to be thin so you can look good on the beach this summer. That's too distant, too far away, too nebulous when it comes to the choice of whether to eat one slice of pizza for lunch today or two.”

The same applies to the consequences of smoking. “It's very hard to put aside a strong urge to smoke and think about the chance that you will get lung cancer or heart disease 10 to 20 years from now. … A person can easily rationalize that this one cigarette or one piece of cake is not going to sabotage my efforts,” said Dr. Volpp.

The answer, then, is to provide short-term rewards for engaging in healthy behaviors, the experts said. That can be accomplished on a systemic level, by employers or insurers paying people for going to the gym or quitting smoking.

“A lot of companies are exploring different types of wellness programs. For example, companies will have their employee pay for a membership in a health club and then the more that employee uses the health club, they get money back,” said Dr. Loewenstein.

The same idea can be used by individual patients or physicians. A person who wants to lose weight could set up a system in which they give money to a friend to hold, and every time the dieter fails to achieve his or her short-term weight loss goal (such as losing a pound a week), some of the money is given away to charity.

In some cases, the concept can work even without the financial incentives, said Dr. Loewenstein. “It's amazing how much people, and not just children, care about praise. As ridiculous as it might sound, you can even change adults' behavior with gold stars. If the patient feels as if their physician is a) giving them strong advice on something and b) keeping track of whether they are doing it and praising them when they comply, they will respond.”

“It's very important for the feedback to be fairly frequent, ideally at about the same frequency as the behavior you are trying to change, although that isn't always possible,” he added.

The type of feedback offered may have an impact on public acceptance of these ideas, however, noted Dr. Volpp. Designing incentive programs in ways that consider fairness is important. “What about the people who are nonsmokers? How will they feel about rewards being given to people who are smokers not to smoke but not receiving rewards themselves?” he asked.

One response is that in nearly all group insurance arrangements nonsmokers currently subsidize health care costs of smokers through their insurance premiums. A reduction in the smoking rate would also make non-smokers better off, Dr. Volpp explained.

Of course, any idea that offers the possibility of lowering health care costs and improving outcomes will interest insurers, and insurance companies are exploring these concepts, especially in the area of medication compliance, said Dr. Brennan, chief medical officer for Aetna.

“The average person is taking about 50% of their medications properly within six months of when they were initially prescribed. We're trying to think of ways to create reasonable incentives for people to take those medications,” he said. Aetna is currently implementing a study with Brigham and Women's Hospital to determine the impact of eliminating copayments on medications for high-risk chronic disease patients.

Defaulting to difficult decisions

Health behavior may be the most obvious example, but the difficulty that people have envisioning the future causes problems in other areas of health care, too, said Eric J. Johnson, PhD, professor of business and co-director for the Center of Decision Sciences at Columbia University.

“It's not something you sit around thinking, ‘What if I need to have surgery?’ or ‘Which kind of chemotherapy would I want should I ever be diagnosed with cancer?’ So people make up their minds based on what is available at the time they make the decision. What that means is that the way the question is asked, when it's asked, how it's asked, can go a long way in determining what the answer will be,” he said.

When asked to make such a tough choice—or any choice, really—people tend to go with whatever option is the default, Dr. Johnson and other experts agreed. For example, in the U.S., where people agree to be organ donors by opting in, participation rates are much lower than in European countries, where those who don't want to be donors have to opt out. (Dr. Johnson and colleague Daniel Goldstein, PhD, discuss default options in a Policy Forum in the Nov. 21, 2003 Science, online.

That aspect of human nature offers a wide range of opportunities to affect health. “Because the way that options are presented inevitably influences the decisions that people make, and the decisions that people make inevitably influence their welfare, there are tremendous opportunities to improve people's welfare by manipulating the ordering of options or the way options are presented,” said Scott D. Halpern, MD, PhD, an ethicist, epidemiologist and critical care physician at the University of Pennsylvania.

HIV screening recommendations are one example of such default-setting. In September 2006, the CDC suggested that physicians make HIV testing a routine part of clinical encounters. Patients who don't want to be tested can still choose not to be, but by testing everyone who doesn't opt out, individuals will benefit by being diagnosed earlier, and society will benefit as a result of reduced transmission, Dr. Halpern said.

Dr. Halpern sees numerous other potential applications at hospitals. “For all hospitalized patients who meet certain criteria, such as being older than 65, a nurse could automatically go to those patients' rooms and offer to administer a pneumonia vaccine,” he said. “That's an easy one because widespread pneumococcal vaccination is beneficial and quite cost-effective.”

Some uses of the idea would cost nothing at all, rather, they simply require a reevaluation of traditional practices. “For patients in the ICU, it's very clear that keeping the head of the bed elevated dramatically reduces the risk of pneumonia. But you walk around your average ICU and the way that beds are positioned by default is flat. There's no rhyme or reason for that. It's just the way things have always been done,” said Dr. Halpern.

The concept also works in office practice to enhance compliance with follow ups, testing and specialist care. “I could walk out and say, ‘Give us a call in six months for the follow-up appointment’ or I could say, ‘Let's make an appointment now and if anything changes, let me know.’ I suspect the latter will get many more regular follow-throughs,” said Dr. Johnson.

“As soon as you realize that there's no such thing as a no-default option, a physician can set defaults in ways that will be in the patient's best interest. That's true for almost any exchange in health care,” he added.

Hurdles to implementation

So why aren't all the beds set to 30 degrees and appointments scheduled automatically? Partly because these ideas are new, and partly because, despite the rationality of the ideas, people are uncomfortable with someone crafting their choices and setting the defaults in a deliberate way, the experts said.

“Someone is making a decision based on their own values as to what the best choices are. That is paternalistic. There's no question about it,” said Dr. Halpern. “The problem is, and what I think most people don't realize, is that there's not really a viable alternative to that kind of paternalism. Either you set a default intentionally or you leave defaults as they are, which means you're leaving welfare to chance.”

The other big question is who should set the defaults. Government agencies such as the CDC and insurers are obvious candidates, but additional issues arise about what their priorities would be in setting the options. Potential benefits to individual patients would have to be balanced with both societal good and cost-effectiveness.

“The thorniest issue is that there is some potential for abuse in default-setting. Those who are in a position to set the defaults, whether it be the government or a private organization, might set the defaults in a way that benefits themselves. For example, a health insurance company might set the default insurance policy as the one that maximizes their own revenue,” Dr. Halpern said.

The best protection against that risk is public education about the significance of defaults, along with disclosure of how and by whom defaults were set, explained Dr. Johnson.

There are also logistical and practical issues to be worked out both on the setting of the defaults and the other applications of behavioral economics in medicine, such as paying for smoking cessation, the experts said.

“How do you actually monitor changes in behavior? How do you set up frequent feedback intervals without significant costs and logistical challenges? Those are all things that really need to be figured out both in terms of the basic science and the translational aspects,” said Dr. Volpp.

Through a variety of randomized controlled trials and other studies, he and other researchers hope soon to have answers to at least some of those questions. “We're still in the embryonic stages of building an evidence base on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different approaches. We hope before long to create a more systematic base of evidence with a menu of options,” Dr. Volpp concluded.